Cracking the City Code

This was a guest edit of the exceptional Exponential View, a weekly series of essays and podcasts run by Azeem Azhar.

Challenging the power structures of megacities

Hi, I’m James. I feel particularly fortunate that Azeem asked me to contribute to Exponential View this week on a topic I’m not only interested in, but feel emotionally attached to. As a partner at Balderton Capital, a venture capital firm based in London and as a Trustee at Demos, a think-tank focussed on connecting policy to the broadest possible population base, I have a professional interest in understanding how power is shifting from cities to regions. I also have a personal stake in challenging the power structures of megacities. Growing up in South Manchester, I didn’t visit London, the economic, political and cultural capital of the UK, until I was 18.

Unlike many other financial asset classes, venture capitalists are highly engaged with their investments. It is a hyper-local service. It is only a semi-joke that investors are unwilling to drive more than 30 minutes for a board meeting. Much of the venture industry is predicated on the idea that putting enough intensely bright and ambitious people into the same room will result in world-changing businesses. The economic returns from this approach have been astounding. In the thirty years to 2017, venture capital has returned 19 per cent annually at lower volatility than the major stock indices.

There are now clearly a set of cities, San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, London and the like which have seen accelerating returns to scale and dramatic growth in complex, innovative businesses supported by the venture capital that finances them. In the process, many have become the economic engines for their respective nations.

For the last few decades, like modern-day Dick Whittingtons, some of the best and brightest have flocked to these centres of industrial and innovative power.

Democracies don’t tolerate such ongoing concentrations of power. The UK government, under Boris Johnson, has made ‘levelling up’ between the capital and the regions a key part of its policy. Donald Trump came to power, breaking the ‘Blue Wall’ while losing the popular vote in most of America’s major cities. The on-going protests in Paris of the Gilet Jaunes also reflect the political clash between regions and major cities. What mix of policy changes, private interventions and technical innovation might tilt the balance of economic power away from a nation’s largest cities?

Big cities, big issues

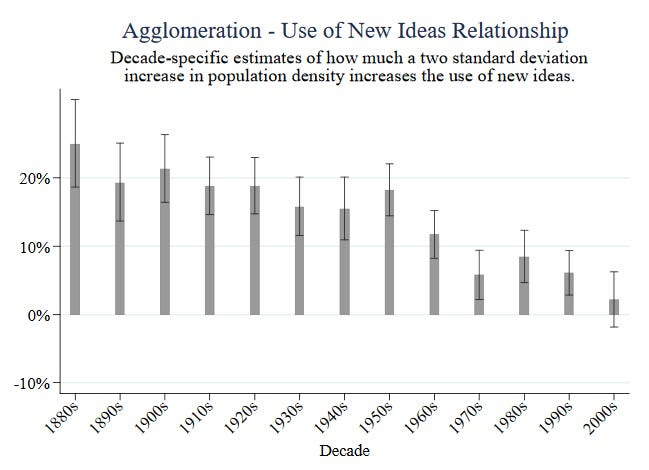

In knowledge economies, competitive advantage tends to be gained from the speed at which ideas and behaviours can spread. In the intensity of a city where you minimise travel time and maximise exposure to new people, the chance for serendipity, of bumping into those people with the skills and resources to support you, increases multi-fold.

There is now more wealth within the small city limits of New York than the whole of Canada; London generates the same GDP as the Netherlands, and were Tokyo set adrift as a nation on its own, it would be the fifteenth largest economy in the world. Productivity in London is the highest in the UK, more than 50 per cent higher than large swathes of the former industrial heartlands of the country.

At the same time, inequalities in both employment and welfare with people living in non-city regions have widened. (Median household income in San Francisco is approaching $110,000 per annum; nearly double the US average of $61,987 and almost 2.5 times that of West Virginia, the least well off state.)

Many don’t see a problem with this. Large cities produce enough economic wealth that, through a fair and redistributive tax system, can be used to support other parts of a country. The average Londoner pays £3,070 (almost $4,000) more in tax per year than they receive in state-services for instance.

There are countervailing forces: large cities are running into real issues. The sheer cost of housing means ‘superstar cities are driving people away.’ The net domestic population outflows from California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois dwarfs other cities, according to this detailed analysis by Justin Fox. (One reason these states’ populations don’t decline is because of immigration, and another is because of the birth rate.)

Commute times are lengthening. Almost all major cities over the last few decades have both promoted themselves as a great place to live and work, while simultaneously refusing to build any new housing—a policy-duo bound to fail.

The limits of city-led growth are perhaps most evident in San Francisco. While it may have been home to some of the world’s fastest-growing companies in the last two decades, San Francisco seems to be single-handedly disproving the theory that cities, like software companies, have economies of scale. And interestingly, Silicon Valley seems to be losing the edge over other innovation hubs. While San Francisco saw rapid population growth of 7 per cent in the 1990s and 11 per cent in the 2000s, the population growth has since slowed to a crawl.

In a recent comment piece and in a new book, Golden Gates, Conor Dougherty of The New York Times captures the problem through the heated exchanges in Californian town-hall and council meetings, where local residents hold up new housing developments, dragging out proceedings until eventually the projects are abandoned.

Finding the right recipe

It isn’t clear that any nation, yet, has the right recipe to address the balance of innovation, creativity, wealth-creation and power between larger cities and the rest. But here are three things that could make a difference:

1. Housing: A recent report from the Centre for Cities, a UK think tank, argues that, outside of London, the UK’s largest cities and towns are no longer becoming more productive as they get bigger, with GDP per employee in Manchester lower than that of workers in Swindon and Reading, towns a fraction of its size. In terms of housing at least, Singapore is amongst the world’s most successful modern city-states. Its public housing programme, in particular, has drawn international praise, achieved through a combination of policies. The less acceptable ones for many Western countries include strong central Government powers to acquire land, with 90 per cent of the land that has been built on being Government-owned, and with the on-going ability of the Government to enforce the sale of land for development pretty swiftly.

But of more interest to Western Governments might be Singapore’s merit-based system, where developers are awarded merit-stars, and for every merit-star earned on a project, the contractor would enjoy a 0.5 per cent bidding preference when tenders were evaluated, rewarding consistent performance.

If California is going to build 100,000 homes, it is going to have to borrow some of these approaches at the very least.

While in Germany, France, and the United States, there is generally still a positive relationship between city size and productivity, the link is weakening. It is clear that two of the largest issues are housing and transportation.

2. Transportation: Effective commuting within cities and between cities is critical. The Open Data Institute recently identified that in Britain, large cities do see the productivity gains we would expect their scale to indicate. The reason: poor public transport infrastructure. At peak transit times, Britain’s second-largest city, Birmingham, behaves like a city a third its size.

Commutes for urbanites are getting longer, according to the global mobility software company Moovit. Istanbul now tops the charts for the city with the longest average commute to work, hitting 72 minutes per trip, but cities across the world are slowing down as they grow, too.

One of the biggest recent shifts in intra-city travel is micromobility. Questions may remain as to the sustainability of either the unit economics or environmental impact of scooter companies, but they are certainly having a significant impact on intra-city mobility. Voi scooters estimated that 25 per cent of their users in Europe replace a car or taxi journey with a scooter ride, with some percentages even higher in particular cities. Copenhagen has set out plans to invest in a range of micro-mobility programmes, with a commitment to over 50 per cent of all rides be made through such a model by 2025, as part of its efforts to become a carbon-neutral city.

For inter-city travel, will we soon fly? Last week, Wisk, a joint venture between Boeing and Larry-Page’s company Kitty Hawk, signed a deal with the government of New Zealand to conduct a flying taxi trial using its all-electric, self-flying aircraft Cora.

How many of us will choose the 10 mile, 1 hour commute in a car, when we can live by a beach 60 miles out, and get to work in 20 minutes by Cora instead?

3. Innovations in remote working may help. As Nobel laureate, Esther Duflo, has pointed out, even when the financial and career incentives exist, people don’t often move. Most people are tied to their location because of the need to care for loved ones, personal attachment to where they are from, or the simple cost of moving. But today, young people can get access to the thoughts of the world’s leading thinkers and practitioners from their smartphones. Tools that support remote or asynchronous work, like Zoom video conference, virtual presence, Github, Slack and other messaging services may help shift the balance. Pioneer, a completely remote startup accelerator announced this week it had raised capital from the likes of Marc Andreesen and the founders of Stripe, to invest in remote-first teams, rather than forcing founders to huddle together in a small room in San Francisco, as previous accelerator models have worked.

Removing the need to structure where we live around where we work will give people more freedom to choose who they want to live with, and locate closer to the things they enjoy. This could result in the resurgence of communes: groups of friends creating joint-living arrangements where assets are shared.

Similarly, this could lead to the development of ‘hubs of passion’, with people relocating to certain areas to match their interests. Whether you are a passionate supporter of opera or football, you will be more free to live in a community closer to Glyndebourne or Old Trafford. It might not be long before the most expensive properties are not those close to the metro stations that can get you into Manhattan quickest, but rather properties in curated communities, where only people who share particular interests and skills are invited to live.

Minds matter

Universities remain one of the most powerful ways to stimulate regional growth. As Anne Valero and John van Reenen showed in her 2016 study of higher education, a 10 per cent increase in the number of universities increases that region’s income by 0.4 per cent. Providing subsidised centres for learning and experimentation in underserved areas, or as one political commentator put it, creating an ‘MIT of the North’ seems to be one policy level to support region growth.

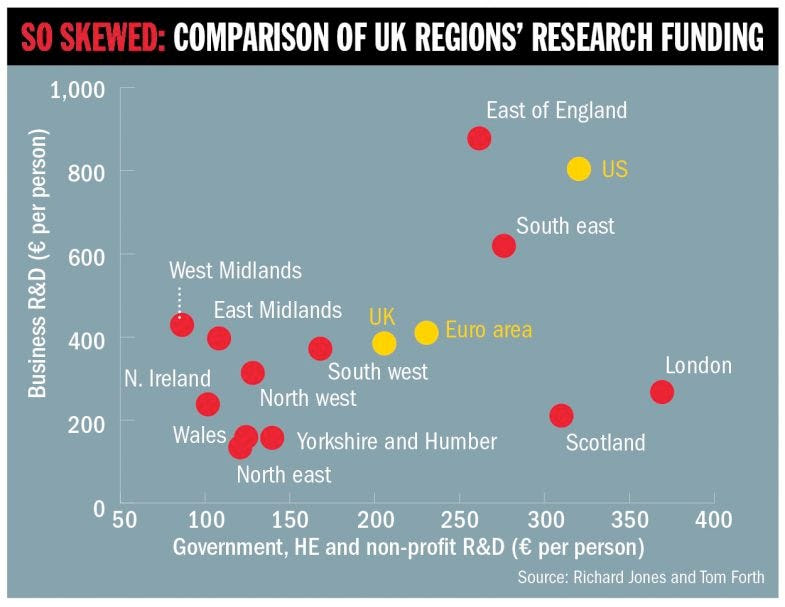

Research shows that, in the UK at least, London is heavily overweight government and public-sector spending relative to business R&D. Rebalancing state-funded research could redress this akimbo distribution.

And where state investment leads, private investment follows. In the US, the ‘Rise of the Rest fund’, announced another $150M to invest in seed companies outside of the usual centres of Boston, New York & Silicon Valley. In the UK, the Government’s British Patient Capital fund, which is led from Sheffield, has similarly committed to deploying a significant amount of their funds into companies outside of the UK capital.

Perhaps the next Dick Whittington won’t have to travel to London to raise that seed round.

I’m open to hearing your thoughts on this key issue in the comments below.

James Wise

@jpwiseuk